Walter J. Hall was the master craftsman who built Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater—but not before he built his own masterpiece.

Before Fallingwater, there was Lynn Hall. Built between 1934 and 1935, this early modernist structure was the creation of Walter J. Hall, who was later hired by Frank Lloyd Wright to build Fallingwater.

While Lynn Hall has lived many lives over the years—as a dance hall, restaurant, and office—it remains a classic example of the Prairie style that Wright made famous. Now, Walter’s legacy—and that of his son, Raymond “Ray” Viner Hall—is receiving renewed attention as two friends set out on an epic quest to restore the historic landmark.

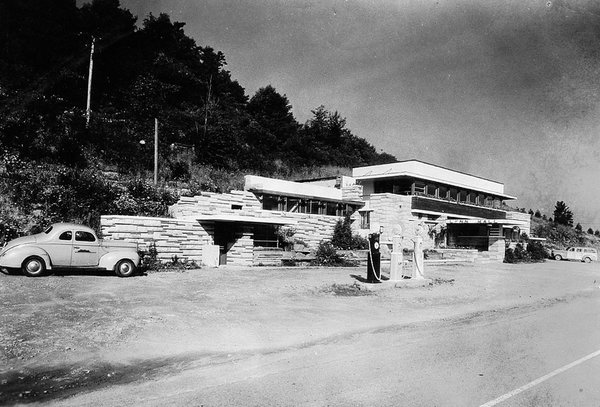

In its early years, Lynn Hall was a popular roadside stop along the famous Route 6 in Port Allegany, Pennsylvania, a small mountain town about three hours north of Pittsburgh.

Photo from Historical Archives, Courtesy of Adam Grant

A self-taught stonemason and builder, Walter imagined carving a country inn out of the Pennsylvania hillside, letting the site topography guide his plans. Lynn Hall fulfilled this vision with an ingenious design that flows with the landscape inside and out—both figuratively and literally.

Walter integrated organic features in ways that went beyond aesthetics—from a rainwater collection system that ends in a waterfall, to an interior pond fed by a natural spring. Marks of the structure’s Prairie style include strong horizontal lines showcasing broad stretches of glass, as well as varied ceiling heights and other uses of the expansion/compression technique.

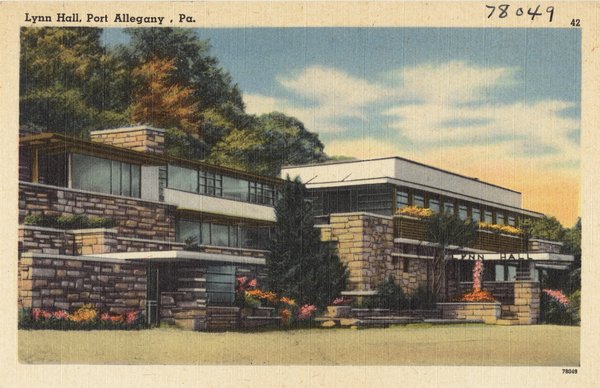

A historical postcard of Lynn Hall—a true destination for travelers and locals back in the day.

Photo from Historical Archives, Courtesy of Adam Grant

At first, Lynn Hall was a restaurant and dance hall, with the early automobile age fueling its popularity as a roadside stop for locals and travelers alike. Declining business following World War II eventually led Walter to convert the building into an office for himself and his son, Ray, who had by that point started a design and building firm of his own.

While the property stood resolute for decades, it went mostly unused after Ray died in the early 1980s, and it slowly deteriorated as the natural world crept in.

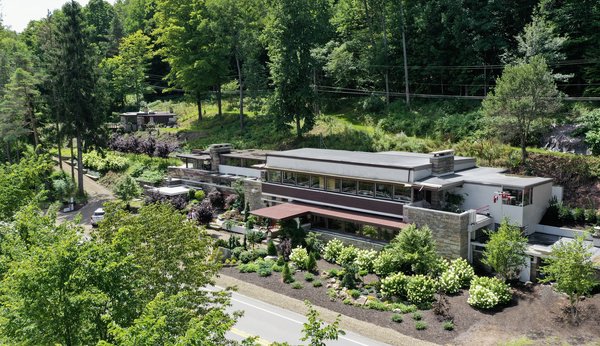

A recent photo shows the main structure and adjacent cottage, both of which were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007. At that point in time, this view of the property would have been hidden by dozens of hemlocks encroaching on the building.

Photo by Adam Grant and Rick Sparkes

See the full story on Dwell.com: Before & After: The Epic Quest to Restore Walter J. Hall’s Legendary Lynn Hall

Related stories:

- Modern Shades and Draperies Integrate Seamlessly Into a Houston Renovation

- A Timeworn Brownstone in Brooklyn Becomes a Growing Family’s Sanctuary

- A Classic Midcentury Home in Napa Gets a Kitchen That Complements its History