Willow Technologies is a material research and building technology practice that has been selected as part of ArchDaily’s 2023 Best New Practices. Founded by Ghanaian-Filipino designer and architectural scientist Mae-Ling Lokko, it operates in the gap between research, development, and diffusion of bio-based building materials. Working with agro-waste and bio-based materials usually incurs technical questions regarding scalability, industrial production, standardization, fireproofing, and mechanical strength. Exploring this data is where Willow Technologies situates itself, but peculiarly through the lens of developing regions in West Africa. Through comprehensive works with coconuts, moringa, rice, and other indigenous crops, Lokko’s practice has been able to investigate and catalog the material character of various crops, their possible by-products, local transformation techniques, and the prospect and challenges of scalability as building materials.

Cconut Panels-grounds-for-return-willow-exhibition. Image © Selma Gurbuz

Cconut Panels-grounds-for-return-willow-exhibition. Image © Selma GurbuzMae-ling explains that achieving scalability of agro-based materials can only happen in parallel with stimulating demand through the understanding and education around these materials. This was Willow Technology’s foundational idea behind exploring the use of coconuts, moringa, and rice agricultural by-products in a country where the commercialization of indigenous species was constantly decreasing due to the influx and marketing of imported hybrid food species. “How to induce the demand and productive use of indigenous crops and agricultural by-products in Ghana” became a research question for the practice, as only through this could the crop generate enough by-product quantities to be scaled into building materials.

As part of a COP27 Call for projects highlighting flooding through the British Council, Willow employed rice plants and coconut pith as core water-retention and flood-tolerant components as part of a bioswale project in the Efua Sutherland Park in Accra, Ghana. Working with a leading African chef, Selassie Atadika, Willow collaborated with the Midunu Institute to source 126 sessions of rice from the Africa Rice through the World Crop Trust and implemented them as green infrastructure in a flood-prone section of the park. The project involved designing and installing bioswale to slow down water by planting flood-tolerant rice alongside other local species. Through this demonstration, Willow Technologies engages in the education of local and global participants, including Ghana’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Scottish architect Tom Morton, students from Ashesi University, and Glasgow’s Mackintosh School of Architecture.

Related Article

Returning the Building to the Soil: an Interview with the Architect and Scientist Mae-Ling Lokko

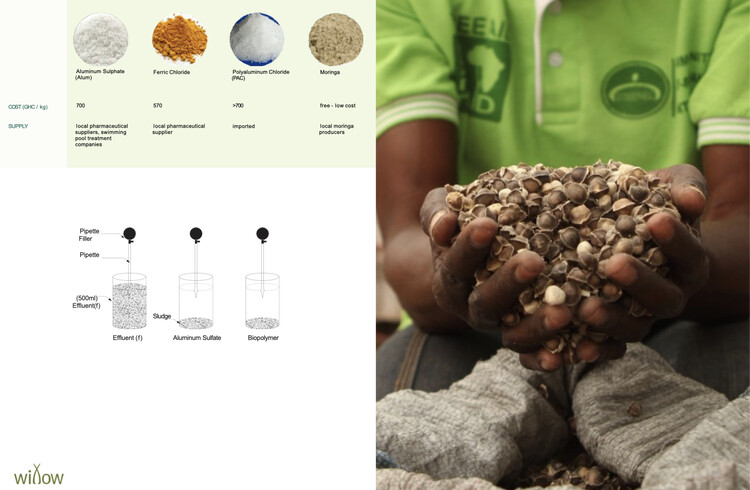

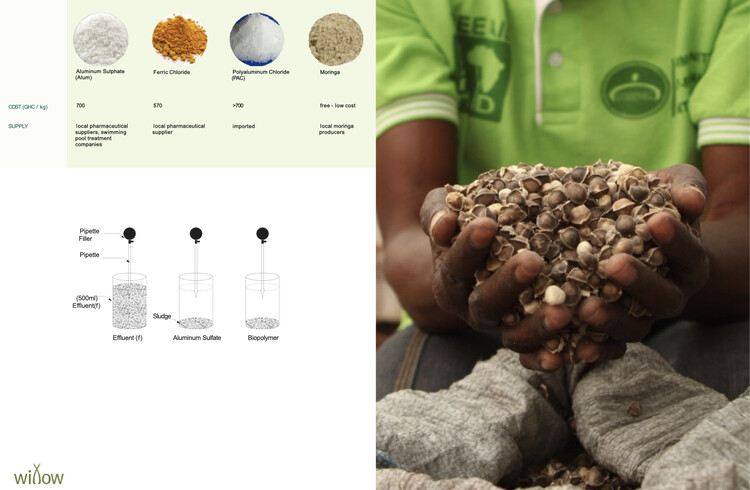

High demand for local food products can increase the prospects for by-products with broader applications. This is exemplified by Willow Technology’s exploration of by-products from moringa, a widely popular tree in Ghana that is typically used for tea, oil, herbal, and medicinal purposes. When the oil is extracted from moringa, a by-product called press meal or press cake is left behind. This flour-like substance can be used as a flocculant to treat toxic wastewater, helping heavy metals and toxic components in water clump together and settle. Willow Technologies’ research and design into moringa flocculants was used in a project to treat the textile wastewater of Global Mamas, a network of batik dyeing women’s home-based enterprises. In a proof-of-concept project, this process reduced the toxicity of their wastewater to below EPA regulations, making it safe to be disposed of in municipal wastewater systems. The remains of the process also form a sludge that presents an opportunity to be used as compressed earth masonry.

Willow Technologies believes that the key to expanding agro-based by-products lies in developing a new distributed production infrastructure for the distributed biomass from food, agricultural, and building cycles. Lokko suggests that reducing production costs starts by intervening in the gap between collecting agro-waste and its quality control, and by designing accessible production methods for them. The company’s initial work with coconut husks as a building material exemplifies these principles. Their projects responded to the coconut boom in Ghana, which left traders dumping tons of husks by the roadside due to the absence of disposal systems. They individually collected these husks from traders for these projects but aim to develop a distributed system of small-scale milling machines at specific points in the city, allowing coconut traders to process their husks and get paid a fee. The husks are shredded into light, fluffy, dried fibers, which are easier to control for material production.

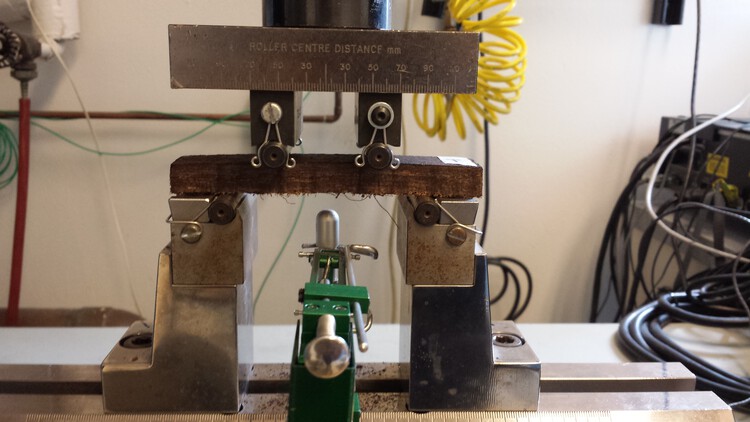

ASTM Testing Coconut Panels. Image © Mae-ling Lokko

ASTM Testing Coconut Panels. Image © Mae-ling LokkoNative mature coconuts in Ghana have a high lignin percentage, which gives them a structural advantage for potential building product applications like medium-density and high-density fiberboards compared to young coconuts from other global producers. Lokko’s practice has harnessed this husk material through thermal pressing methods that make use of bio-based glues to produce low-carbon, non-toxic fiberboards. This process is in contrast to reconstituted wood or plastic board products, which are pressed with glues at higher temperatures and due to the use of synthetic glues release VOCs and toxic fumes that compromise the health of factory workers and building inhabitants.

Despite the various processes involved, the biggest challenge facing Willow Technologies has been changing the perception of these materials from something local to aspirational within the context of Ghana. “Usually, the quickest way to use these materials in buildings is as insulation. But once you hide them in a wall, no one really cares or is willing to pay a high price for them,” says Mae-Ling. “I think there’s a missed opportunity to capture their true value as strong, breathable building skins, partitions, and furniture, by embedding customization that has the potential to attract and seduce people into adopting them,” she adds, noting that design has an important role in shifting cultural perception. This was an approach the practice also used in employing coconut husk fiber boards in projects, using the shape, texture, color, and surface patterns of these panels to add to the mechanical, acoustic, or thermal performance of the product shown in projects like the Yale CEA Nairobi Ecological Pavilion and exhibitions at the Museum of the Future in Dubai.

The Ghanaian-Filipino architect believes that not all materials can or should last forever, and we need to rethink the maintenance value and performance metrics of all building materials. According to Lokko, coating such biobased materials greatly reduces the potential of the unique hygrothermal behaviors of such materials to impact indoor comfort. Such material behaviors are important passive cooling technologies that rely on sorbing and storing moisture during the late evening and early hours of the morning in hot-humid, tropical environments and expelling that moisture during the day.

By comparing the broad properties of bio-based products, such materials have a large role to play in both leveraging abundant local resources and also driving down carbon throughout the production, operation, and end-of-life of a building. Scaling up and normalizing the use of agro-waste and bio-based products in building material applications in Ghana and other contexts will require both bottom-up and top-down collaboration. On the one hand, developing partnerships between stakeholders in the agricultural and building sector are needed to capture such resources and to help upskill local artisans and professionals to become part of a thriving bio-economy. On the other, it will also require governments to play an active role in national and regional policies, to support and incentivize such partnerships and stimulate market demand.