Mexico is experiencing a “renaissance” in architecture and design because of its embrace and promotion of artisanal practices, says designer Héctor Esrawe in this exclusive interview.

According to Esrawe, who runs a studio in Mexico City, the last 10 years have seen Mexican creativity being taken more seriously at home and abroad.

“There is this renaissance where all the creative activities have evolved, and the standard that we can create now in Mexico is being expressed and accepted worldwide,” he told Dezeen.

Esrawe pointed to increasing interest in Mexico’s various cultures and artisanal traditions by the architecture and design community as the key element in the success of the country, which just last month held its 15th annual design week.

“We started to look inward, we started to value and appreciate what we were made up of,” said Esrawe.

“We started to relate to our ancestors, to our narratives, and understand the vastness and richness and skills that we have as a culture, and I think that eventually became contagious.”

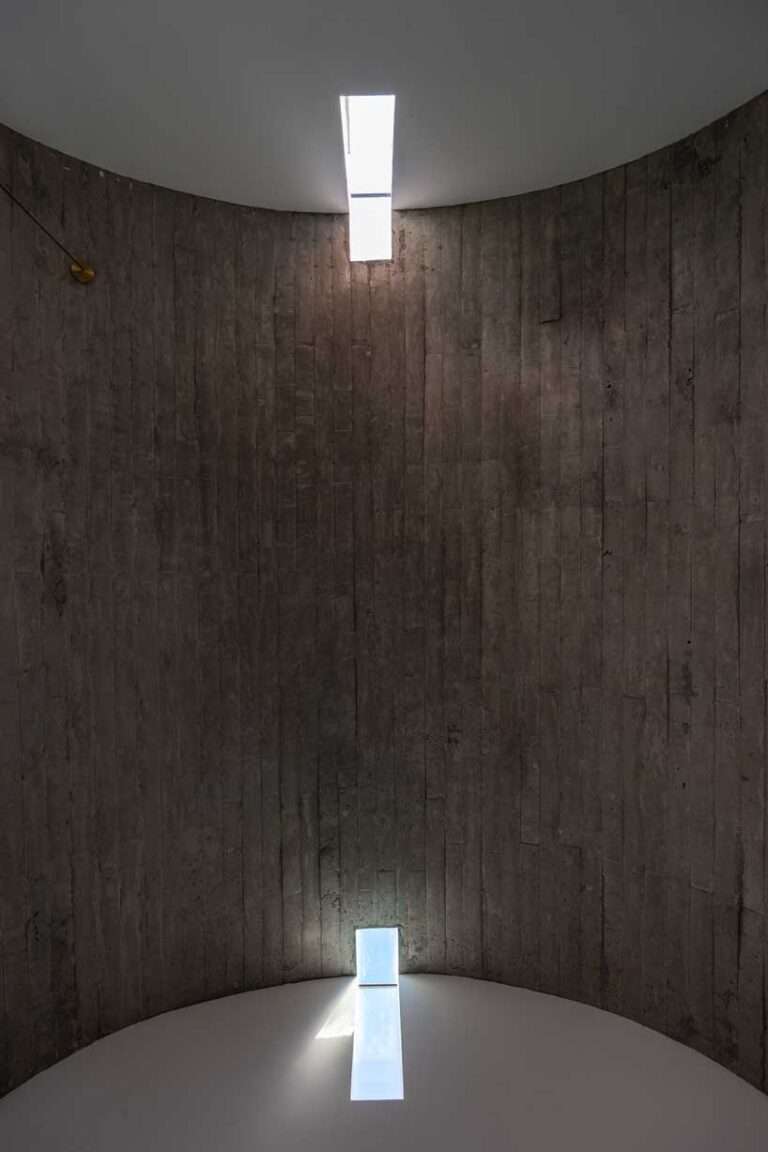

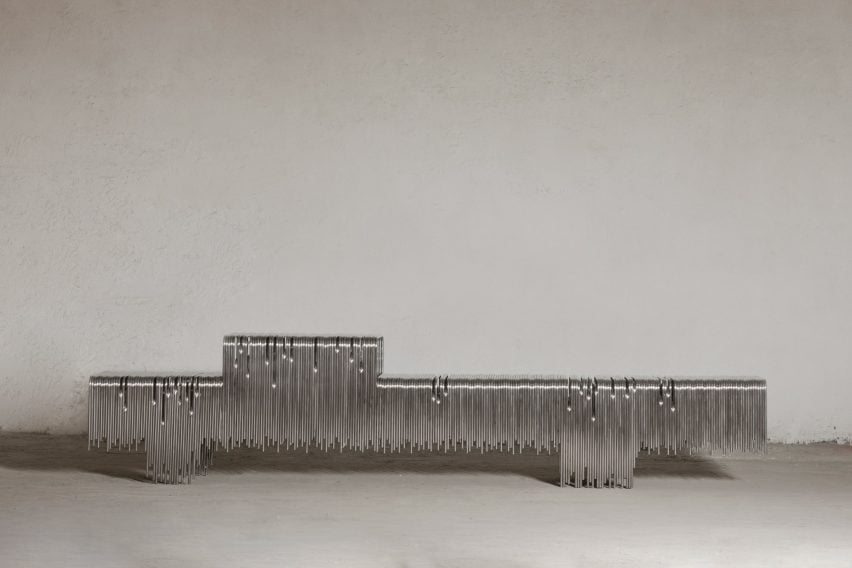

Esrawe is one of a handful of architects and designers at the forefront of a new wave of Mexican design. He is known for his sculptural architectural and design work that incorporates artisanally crafted materials such as wood, bronze and stone.

An important aspect of Mexico’s design renaissance, according to Esrawe, has been supporting handmade objects and artisanal processes in the country without falling into the trap of mass-producing cultural objects for consumption.

He said that artisans such as stone workers or wood carvers are often “put on a pedestal” but expected to conform to the needs of mass production.

Instead, Esrawe argues that the collaborations between designers and these groups, which have fed into his own practice, should push everyone towards new forms and provide artisans with a platform to get the best results.

“We should create a dialogue in a horizontal way, and create a platform that allows for the artisan to express and create those collaborations – it’s extremely rich and powerful,” he said.

“I see [collaboration] in a positive way,” he added. “I see more experimentation. I see new languages appearing.”

Collaborating with artisans comes with challenges that must be respected, he acknowledged.

“There’s a risk on the side that has to do with the ambition of more and faster,” he continued, adding that designers need to understand that working with materials like metal and stone in small-batch operations takes time.

Esrawe said he has also struggled with a conception among Mexicans that things produced natively should be cheaper.

He recalled that when he opened his gallery in the early 2000s people would ask why the work was so expensive, with greater value typically placed on objects from countries like Italy.

“There was this conception that we were only labourers and not so creative and didn’t have the power to become something that could challenge another culture, which was more ‘stylish’,” he explained.

However, two moments marked turning points for Esrawe’s own perception of the potential of Mexican design and architecture.

The first was the ascendency of chef Enrique Olvera’s restaurant Pujol. For the first time, the best restaurant in Mexico was by a Mexican chef.

“This has been a transformation that started happening in parallel in many activities, in many activities that you can perceive as unrelated like food, but then in others that are more connected, like art, fashion, architecture and design,” he said.

The second was his experience of an exhibition in Finland.

“For me, it was completely new to see in the same gallery an artist, a designer, and an artisan exhibited together,” he said.

“That was not common for me. That was not common in Mexico. So in a way that shaped my understanding of how it should be.”

Since then, Mexico City has become a hotspot for design and last year, Masa, a collective run by Esrawe and designers Age Saloe and Brian Thoreen, put on a show featuring contemporary and historical Mexican art and design underneath the Rockefeller Center in New York City.

Esrawe said that this wide recognition has been accompanied by an influx of designers into the city, all wanting to explore the potential of production in Mexico.

“It became more attractive,” he said.

Cruciform cabinet anchors The Loma Residence by Esrawe Studio

Cruciform cabinet anchors The Loma Residence by Esrawe Studio

“Many other artists from all over the world have moved to Mexico, understanding that those [production] possibilities are disappearing in many cultures,” he continued, referencing again the wide array of artisans and craftspeople in the country.

“You cannot even think of that in the States, for example.”

Esrawe has in recent years further dedicated himself to the principles of smaller production and artisanship.

He recently closed his factory, limiting production to focus more on architecture projects and smaller-batch design items.

“I decided to do this because I fully believe in it,” he explained.

“I believe sometimes you need to burn the ships in order to really practice your principles, or your aspirations or what you believe.”

Esrawe Studio recently collaborated with Productora on a Mexico hotel outfitted with planes of green tile and Cadena on spinning, woven chairs at FORMAT festival in Arkansas.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen’s interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.