By the time Andrew Ashey was seven years old he knew he wanted to be in the world of design. His interest was sparked while going on long drives with his family through the Upper Valley, a region that straddles New Hampshire and Vermont. “I was especially drawn to the contrast between the old New England farmhouses in the hills, the Victorian homes in town, and the Modernist buildings on campus,” he says. “When I asked my dad who created those buildings, and he told me architects did, the idea stuck with me.”

A few years later, on a grade-school field trip to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, it all clicked when he experienced the city’s density and how people moved through it. Many different structures served as inspiration for Ashey, but the Exeter Library by Louis Kahn made a lasting impression. He continues to be surprised by how it manages to convey permanence and poetry at the same time.

Andrew Ashey Photo: Meaghan Peckham

In 2014, Ashey and Anne-Marie Armstrong founded AAmp Studio. Based in Portland, Maine and Toronto, Ontario, Canada, the principals focus on design at multiple scales, from commercial and residential projects to branding. With an emphasis on collaboration, they work closely with clients to provide elegant, intelligent solutions tailored to their needs.

The principals have also created AAnnotated at AAmp, a collection of photographs and reflections that capture the overlooked elements of the built environment, like mismatched gutters, utility boxes, or fragments of ornament stranded in unlikely places.

Much of what is envisioned is never built, and without some type of record these ideas risk being lost. Ashey recognizes that media not only shapes how people engage with the work, it is the lens through which it is preserved. “If I ever stopped practicing architecture I’d still want to document the world around me – telling stories through images and words about the spatial peculiarities that catch my eye,” he adds.

Today, Andrew Ashey joins us for Friday Five!

Photo: Andrew Ashey

1. Whimsy

I’m drawn to moments of whimsy because they make architecture feel human – unexpected, joyful, and a little strange. In a field that often leans toward rigidity or seriousness, a bit of playfulness opens up space for emotion and delight. Whether it’s a hidden ramp, an oddly placed window, or a quirky streetscape like this one I stumbled upon in Catskill, New York, I love design that brings a smile to my face and invites curiosity. These moments remind our studio that architecture doesn’t always have to explain itself – it can simply spark wonder.

Photo: Andrew Ashey

2. Plants

Plants bring life, softness, and time into architecture – they mark the seasons, reclaim hard edges, and remind us that cities and spaces are part of larger ecologies. In urban design, they break up monotony, offer moments of pause, and invite people to linger. I’m drawn to how vegetation can transform a space without architecture trying too hard – simply by letting something grow. Parque México in Mexico City, pictured here, is a perfect example: lush, layered, and full of quiet corners, it shows how plant life can shape atmosphere as powerfully as any building. I try to carry that sensibility into both my work and my home, as a way to stay connected to the natural world, even in small moments.

Photo: Andrew Ashey

3. Empty Spaces

I’m drawn to the quiet tension of spaces not being used – rooms left empty, corners paused in time, architecture waiting for purpose or exhausted from use. There’s something almost ghostly about them, yet they still hold presence, still shape the world around us. This unused classroom in the Netherlands, for example, feels suspended in time – its furniture untouched, light filtering in softly, the sense of past activity still lingering.

For me, this extends beyond spaces built for people, to those made for things – warehouses, silos, infrastructure – structures that often sit on the edge of our awareness, designed for utility but carrying a strange, haunting beauty when left still. This is core to a lot of research AAmp is doing at the moment. These spaces remind me that architecture continues to resonate even in absence – revealing traces of past use, forgotten intention, or quiet potential. It’s architecture beyond purpose.

Photo: Andrew Ashey

4. Accidental Design

I’m fascinated by the kind of design that emerges not from planning, but from daily living – when architecture gets used in ways no one anticipated. A worn path through a lawn, a bench that becomes a gathering spot, or sunlight hitting a wall just right at a certain hour – these unintentional moments reveal how people truly inhabit space.

Even in my own home, moments like the one pictured here – a room mid-painting, taped and in flux – reveal how a space can take on a new character simply through the process of being lived in. They remind me that good architecture isn’t just about control or precision, but about allowing room for the unexpected, for life to leave its mark. It’s often in these accidental gestures that spaces feel most alive and personal.

Photo: Andrew Ashey

5. Flying Over Cities

I travel often, and flying over cities offers a rare chance to see the urban landscape as a kind of composition – layered, abstract, and revealing. From above, patterns and densities shift, and the familiar becomes strange: grids dissolve into chaos, neighborhoods blur into infrastructure, and scale takes on new meaning. The descent into Los Angeles, pictured here, captures this perfectly – the city’s vast sprawl stretches toward the distant mountains, textured with freeways, rooftops, and scattered pockets of green. It’s both disorienting and captivating – a mix of form and function that reveals something new with every landing. There’s often a striking contrast between the dense urban fabric and the city’s edge – a threshold where the built environment gives way to the landscape in curious ways.

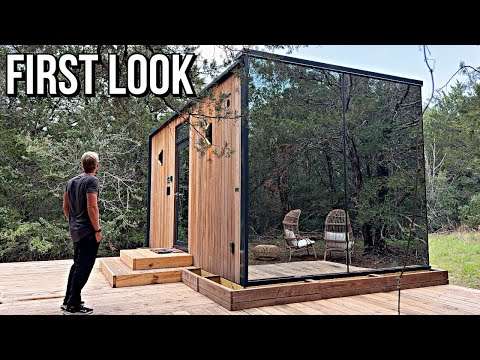

Works by Andrew Ashey and AAmp Studio:

Photo: Maxime Brouillet

Ell House

Ell House is a 2,200sf vacation home on Lake Ontario in Prince Edward Country. Its dark silhouette and gabled form contrast its rural surroundings while echoing the local vernacular of the area. Its L-shaped layout responds to prevailing winds, with one wing shielding the other to create a protected indoor-outdoor living space. The house is organized into two wings – one for communal areas, the other for private rooms – offering intuitive flow and a strong sense of shelter. A minimalist interior of light concrete, white walls, and pine contrasts the charred cedar exterior, creating warmth and clarity throughout. Carefully placed openings frame the landscape as living art, grounding the home in its natural setting.

Photo: Doublespace Photography

Bessborough Residence

Bessborough Residence – a 3,300-square-foot red-brick 19th-century home in Leaside, Toronto – was thoughtfully preserved, fully renovated, and expanded for a young family. A modern rear addition mirrors the original form while introducing double-height spaces, an open plan, and increased natural light. A two-story glass element marks the transition between old and new. The addition incorporates reclaimed brick from a former garage and rich gray board-and-batten siding to complement the historic structure. Inside, warm white walls and oak floors are accented by deep blues, soft olives, and crafted moments like a barrel-vaulted hallway, oak-paneled breakfast nook, and zellige-tiled ensuite bath.

Photo: Dale Wilcox

Sunnyside Townhouse

A narrow 100-year-old semi-detached home in Toronto’s Roncesvalles neighborhood was completely renovated and expanded to create a vibrant, light-filled space for a growing family. The redesign transformed a series of dark Victorian rooms into an open-plan layout, with a third-floor addition housing a new primary suite and private roof deck. Color, millwork, and materials were used playfully throughout, reflecting the clients’ love of textiles and quilting. A dramatic dark staircase anchors the home, contrasting with bright interiors and guiding a procession through varied textures and spaces.

Photo: Brooke Holm

Municipal Grand Hotel

Municipal Grand is a 44-room boutique hotel housed in a landmark mid-century Federal Savings Bank, carefully restored and reimagined. The predominantly concrete building anchors a prominent corner in Savannah, with its bold form softened by curved walls and arched openings. Interior spaces draw inspiration from original terrazzo floors, mosaic tile columns, and mid-century wood paneling and metalwork. Public areas – including the reception, bars, mezzanine lounge, and rooftop pool – celebrate Savannah’s character through texture, color, and pattern. Guest suites are warm and inviting, with rich wood, stone, terrazzo, and textile accents.

Photo: Adam Szafranski

The Ramble Hotel

The Ramble Hotel, located in Denver, also houses Death & Company’s second location. The project involved close collaboration with Death & Co and Gravitas Development Group to translate the original NYC bar’s distinctive brand identity into a new type of space, featuring rich textures, plush seating, and atmospheric lighting. Situated in the emerging RiNo arts district, the Ramble’s open-all-day lobby bar functions as both a social hub for locals and a gathering place for guests. AAmp’s design, in collaboration with Avenue ID, crafts an intimate, layered experience – blending the heritage of Death & Co within the hotel setting.

Photo: Erin Little

The Danforth

The Danforth is a neighborhood restaurant in Portland’s West End composed of three distinct yet cohesive spaces: a bar, a lounge, and a three-season patio. Each area offers a unique atmosphere – light and energetic in the bar, moody and soft in the sunken lounge, and flexible and open on the heated patio – while unified through material continuity like a shared wainscot datum. Rounded booths and curved millwork ease the angularity of the existing building and add texture and warmth. At the heart of the design is a sense of community, offering both casual and intimate experiences that reflect and serve the surrounding neighborhood.