LEED and Passive House have become gold standards for energy-efficient homebuilding—but some say there’s a better way.

“If you feel like you’ve met the standard, feel free to buy yourself a plaque,” says Michael Maines, a residential designer in Palermo, Maine, who’s the unofficial spokesperson for the burgeoning Pretty Good House building standard. Its members—builders, contractors, and architects—assemble monthly to dissect, often over a beer or two, the finer points of building a carefully considered home. Topics range from the benefits of panelized walls to concrete-free slabs, but all point back to energy efficiency and a rubric that is, on an ongoing basis, up for discussion.

It all began sometime around 2009 when Dan Kolbert, a builder from Portland, Maine, became disenfranchised with home rating systems. “People were getting caught up—they were losing the forest for the trees, and all for the sake of the certification,” he says. Still, Kolbert saw the immense value in programs like Passive House— airtightness, insulation, and mitigating thermal bridging are paramount to energy reduction.

So he began moderating town hall–style gatherings to open-source the fundamentals that go into a well-built home. The movement draws its name from the first topic of conversation: “What makes a pretty good house?”

A project by Michael Maines in New England adheres to Passive House principles and points agreed upon by local building experts.

Courtesy of Michael Maines

A decade later, that prompt has become a springboard for a growing network of homebuilders across the country. Michael Maines has since started his own group, BS & Beer (BS stands for Building Science) that features top building experts and airs weekly via a Zoom link. Others across the U.S. have followed suit with similar discussions focused on their own regional building standards. We spoke with Michael to learn more about how Pretty Good House started, what’s changed over the course of 10 years, and why it will never offer certification.

What sparked the idea for Pretty Good House? Why another building program?

Maines: Sometime around 2009, a few guys in Portland, Maine, started getting together to talk about building science just because it’s expensive to go to conferences, and there were so many other ways to share ideas and tips. Dan Kolbert had actually done a LEED project at that time, and had just finished a Passive House project—these were the early days for Passive House. He also finished the first Living Building Challenge school in the nation, so he knows what he’s doing. But at that time, he saw so many people doing all sorts of things for the sake of certification instead of it being the right thing to do.

Certification programs are complicated and cost money. They all have good intentions, but they’re just not widely adopted. So they’re not doing what they need to. With LEED, it was checking boxes—and with Passive House, it was the amount of resources, materials, and consultants you need. And how far you have to stray from how people are used to building. It was just too weird to try to build a green house.

People would say, “if I can’t do Passive House, or if I’m not going to do LEED, I might as well just build code minimum.” We wanted to do better, so we started asking: “what can we agree on that we should be building?” If Passive House is too much, and code minimum is too little, where should we be? So a group of us, in two or three different sessions that ranged from 30 to 70 people, started brainstorming ideas and more or less came to a consensus.

The tenets of a pretty good house are always up for discussion, but the principles remain the same.

Courtesy of Pretty Good House

What are the main ideas, and how is this different from other certifications?

Our idea is to provide some guiding principles. Pretty Good House is less rigorous than those other standards. We try to keep it pretty lighthearted—one of our jokes is if you feel like you’ve met the standard, feel free to buy yourself a plaque. That’s our level of caring about the details. The core principle, though, is balancing expenditures and gains. We basically tell people to make improvements until it stops making financial sense. Insulation is very important, for example, but doesn’t do a lot for you without airtightness. We have an agreed-upon standard for our climate in New England. We do have some prescriptive numbers—if you’re looking for what to do, then we’ll tell you.

But the Pretty Good House standard isn’t just energy performance. It’s also more holistic, along the lines of the LEED program or the Living Building Challenge. They consider everything—from location, to materials, to indoor air quality. So we basically say you should do all of those things too, but we’re not gonna force you to check a box for whether the nearest market is one mile away or two miles away. If you have to drive 60 miles every time you need a gallon of milk, that’s probably not a very smart way to live. So it’s just common sense.

“If you feel like you’ve met the standard, feel free to buy yourself a plaque.” —Michael Maines

Passive House is concerned with reducing energy use to a bare minimum, high indoor air quality, and very high occupant comfort. You could build a passive house out of all foam. You could build it out of baby seals. They don’t care—it’s do you pass the standard? Yes or no. LEED has a checkbox system that, in the past, was easy to game, so you see a lot of LEED-certified buildings that are total energy dogs. But their consultants knew how to play the game, so you get a bunch of projects that probably shouldn’t be considered green.

The Living Building Challenge basically takes that LEED concept of the holistic approach to an extreme. If every building was Living Building Challenge–certified, we’d have no environmental concerns whatsoever. It’s a great goal, but it’s an incredibly difficult thing to reach. For those of us doing high-performance building, Passive House now feels pretty easy.

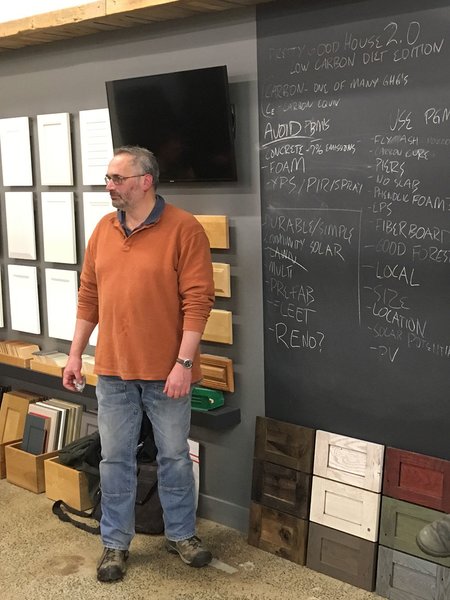

Homebuilder Dan Kolbert moderates a Pretty Good House meeting at Performance Building Supply in Portland, Maine. Here, they discuss ways to lower a home’s carbon footprint.

Courtesy of Pretty Good House

See the full story on Dwell.com: Here’s What it Takes to Build a Pretty Good House

Related stories:

- At This Lush Colorado Home, Every Day Is a Walk in the Park

- This Net-Zero New York Passive House Teaches its Community to Build Green

- Living Vehicle Unveils 3 New Solar-Powered Trailers for Going Off-Grid in Luxury