A new exhibit at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum tells the story of how two midcentury masters met, and how their shared obsessions produced a lasting midcentury aesthetic.

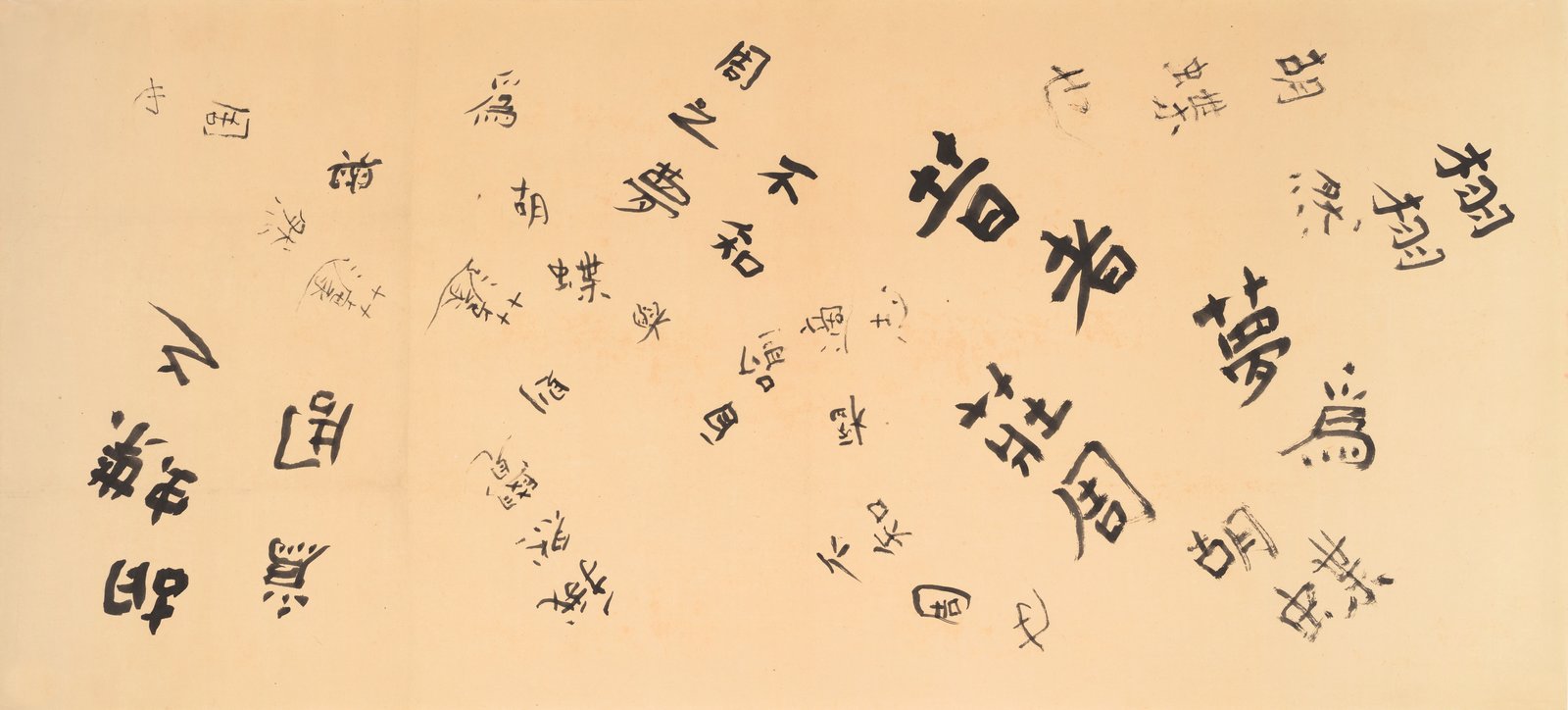

At its core, Changing and Unchanging Things: Noguchi and Hasegawa in Postwar Japan is a story of friendship. The new exhibit, which opens today at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, reflects conversations between two midcentury luminaries and displays more than 100 pieces in all. Renowned designer and sculptor Isamu Noguchi’s paper Akari lamps and stone, wood, and metal sculptures are placed in dialogue with calligrapher, painter, and philosopher Saburo Hasegawa’s prints and paintings—ultimately revealing how their interest in fusing traditional Japanese shapes and concepts with modern, European aesthetic helped shape midcentury design.

Isamu Noguchi with Saburo Hasegawa and other friends, c. 1952

Courtesy of Asian Art Museum, personal prints file

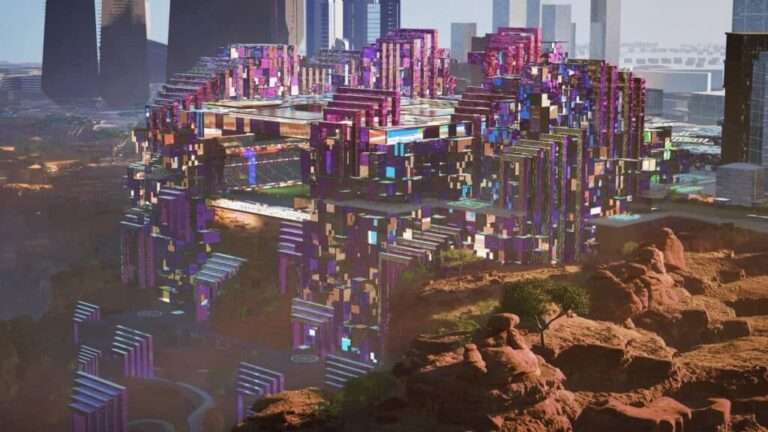

Noguchi has become a household name, but Hasegawa less so, partly due to his premature death in 1957. The exhibit, organized by the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, illuminates how their work intersects (though they never formally collaborated on one given piece). Noguchi first met Hasegawa in 1950, after Noguchi’s voluntary incarceration at an internment camp in Arizona drove him to Japan to find a “purposeful social end” for his work. This sparked an intimate friendship and artistic bond that would not only shape their individual work, but also solidify Eastern influences in Western design.

To learn more about the exhibit, we caught up with Karin Oen, curator for the show at the Asian Art Museum. Here, in her words, are a few things you should know about the artists, the exhibit, and why you need to see the show.

![Untitled [C.I-V], approx. 1955, attributed to Saburo Hasegawa (Japanese, 1906–1957). Photographic prints. Tia and Mark Watts Collection.](https://myproperty.life/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/how-a-friendship-between-isamu-noguchi-and-saburo-hasegawa-helped-shape-midcentury-design-2.jpg)

Untitled [C.I-V], approx. 1955, attributed to Saburo Hasegawa (Japanese, 1906–1957). Photographic prints.

Tia and Mark Watts Collection

How are the two artists’ works presented, and what was the desired effect?

We were able to reconfigure it in a way that makes sense in this museum. Rather than have all of Hasegawa’s work together and all of Noguchi’s work together, we wanted to integrate it.

The goal was to create a relationship between very disparate works, but also create natural pauses to allow people to take in a large amount of work by artists pondering destruction in the atomic age, the terror of war, and how it affects people in a home environment. The pauses allow all of the weightiness to work well with other lighter things: the beauty of materials, the joy of framing specific moments. The Daoist philosophy was lifted out of historical context and incorporated into the work in kind of a playful way, allowing for all of these different kinds of experiences. The goal was to avoid an overwhelming presentation of work after work, but rather, convey that things could be taken in any number of ways. It’s not chronological; it’s about thoughtful grouping. They have a lot to say to one another.

Space Elements, 1958, by Isamu Noguchi (American, 1904–1988). Greek marble. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York/ARS.

Kevin Noble

See the full story on Dwell.com: How a Friendship Between Isamu Noguchi and Saburo Hasegawa Helped Shape Midcentury Design