A creative jack of all trades, London-based Andu Masebo boasts a background in carpentry, metalwork, ceramics, and fabrication that has helped to turn him into the talented product designer he is today. “In one sense, it’s always been quite clear to me that I’d end up being involved in making objects somehow,” Masebo shares. “In another, it was all a bit of an accident.”

That’s because he never intended on working under his own name but rather harbored dreams of being hired by a great design studio once he finished earning his master’s degree in product design at the Royal College of Art. Going so far as to admit he didn’t make particularly great work, Masebo ended up trying to impress interviewers with versions of things that already existed. “It wasn’t until I left and I started to make quite simple objects that I wasn’t trying to impress anyone with that it started to click for me.”

Photo: Ollie Adegboye

Today, Masebo often switches back and forth between the roles of designer and maker as a way to generate ideas and create connections. But surprisingly, he doesn’t feel like his design practice has yet made a clear shift from hobby to career, noting that while it’s his main source of income, it’s also full of contradictions.

The designer candidly shares: “I take the funds from one thing and use them to pay for the next. I work most weekends, but compared to every other job I’ve had, it barely feels like work. And while it’s definitely building towards something, I’m also making it up as I go along.” Masebo posits that perhaps his design work will feel like a hobby if and when he spends more time managing people than making things, which doesn’t sound like much fun.

His extensive experience in making has ironed itself out into a practice that’s “engaged with the way objects come to be, the conditions under which things are produced, and the wider systems that dictate their context beyond their production,” Masebo says. It’s this simplicity and efficiency that mark his work, telling stories that are clear and accessible, shortening the distance between making and understanding.

When it comes to material possessions, Masebo said it’s common for makers of things to want to own them, sharing that he’s typically obsessed with whatever he’s making at any given moment. “Then I’m uninterested in it once I’ve given it all of my attention,” he says. “I think it’s what’s required for me to make things to a level that I’m happy with.” The designer delightfully admits that there is one unexpected item he owns and favors. “I have an Arsenal mirror that, if I’m honest, probably belongs in a pub somewhere. I love the story of how it came into my life, and I love that most people that see it find it so offensive.”

We’re happy to have Andu Masebo join us for Friday Five!

Southbank Centre Aerial View Photo: India Roper Evans

I used to go there a lot as a kid, to free public concerts, reading clubs, and sometimes just to be there on the weekends. I enjoyed it then for how it made me feel while I was there, but it wasn’t until I grew up and developed an appreciation for art and architecture that I understood why it made me feel that way. A building genuinely built for the public to enjoy, it was intentionally designed to be inefficient with its use of space so that it could be interpreted and brought to life by the people that use it. I’m not sure there’s anywhere else you can go in London and experience something so fully without having to spend any money.

A comprehensive study of the various methods and reasons for joining materials together. On the face, it sounds like something unachievable within the confines of a singular book cover, but U Joints manages to do so whilst also telling compelling stories that add to the seemingly banal yet incredibly varied act of joining things together.

Photo: Giovanna Silva

I love Giovanna Silva’s work almost as much as I love Enzo Mari’s. A beautiful film filled with thought-provoking encounters.

Photo: Andu Masebo

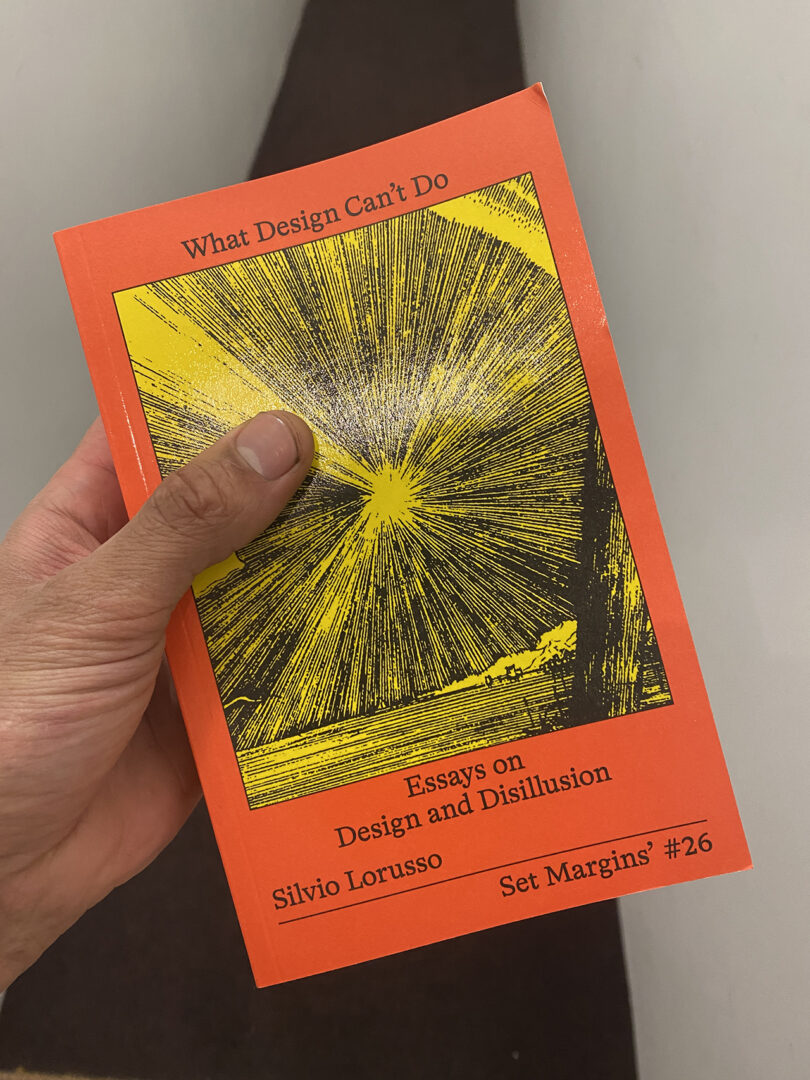

Of all of the design books on my shelf, this is by far the most realistic. It’s not that it suggests that design is futile, but that maybe we should get some perspective before we crack out the Post-It notes.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia Magnus D from London, United Kingdom, Uploaded by BaldBoris

Even though it’s 60 years old, the BT Tower still stands out as one of the most surreal buildings in London. A kind of north star, you can see it from almost anywhere in the city, but strangely, when it was first built, it was technically a state secret. It didn’t appear on any maps and couldn’t be referred to in Parliament for almost 30 years. What I would give to be a visitor on one of its incredibly rare guided tours.

Work by Andu Masebo:

Spare Part Side Table Photo: George Baggaley

Tubular Chair Photo: Atelier 100

Part Exchange at the V&A Photo: Andu Masebo