Bridget Harvey is a maker and practice-based researcher who has been examining repair, hope, and activism since 2012, through practices such as working as a repairer and maker, exhibitions, a practice-based PhD, an artist residency at the Victoria and Albert Museum, public speaking, and repair workshops.

Bridget Harvey

Tell me about your childhood, education, and background and how you first became interested in repair.

In a lot of ways it was all very ordinary. However, I was always encouraged to make things, to tinker with things and to fix things. This might be making ideas that I had, or tie-dying clothes with my Gran, or helping maintain the house. While I was always encouraged to care for my things, repair them, re-use, and repurpose materials, I didn’t consciously notice my interest in repair until much later. I left school at 16, did a screen printing apprenticeship in Philadelphia and some other bits and pieces, then I settled in to a job at Waterstones bookshop for a few years, making and fixing things in my spare time. It was when I had been there for a few years that I decided to go back to studying, first at Morley College in Southwark, and eventually completing my PhD (on repair as practice) at University of the Arts London.

What appeals to you about repairing existing objects versus creating something new?

I guess I do a bit of both now – I make objects from materials from broken things, and I repair things. I do not like waste, and I want to explore and show how we can reduce our environmental impact by approaching making in different ways. In my making, I am really interested in individual agency – how we can use making to interact with and prolong the life of the precious materials we have around us. This can also bounce up the making scale – if enough individuals come together to ask how their things are made and why they can’t fix or adapt them, then hopefully manufacturing practices will change. I also think that the hands-on interaction with materials and stuff is good for us, we can do it alone, together, watching videos, or reading forums, whichever way – but touching the real things around us and understanding them is important.

There are many words for repair with slight nuances in their meaning – mending, fixing, hacking, restoring, repurposing… which do you prefer in relation to your work and why?

I prefer repair, for me this has both the clear direct meaning and also the flexibility. To repair something is to take it to a state that suits the way you want it – so not necessarily the way it was designed to be used, but how you want it to work. I often use the term repair-maker as well, to emphasize the link between the acts of repairing and making something new.

How would you describe this project or body of work?

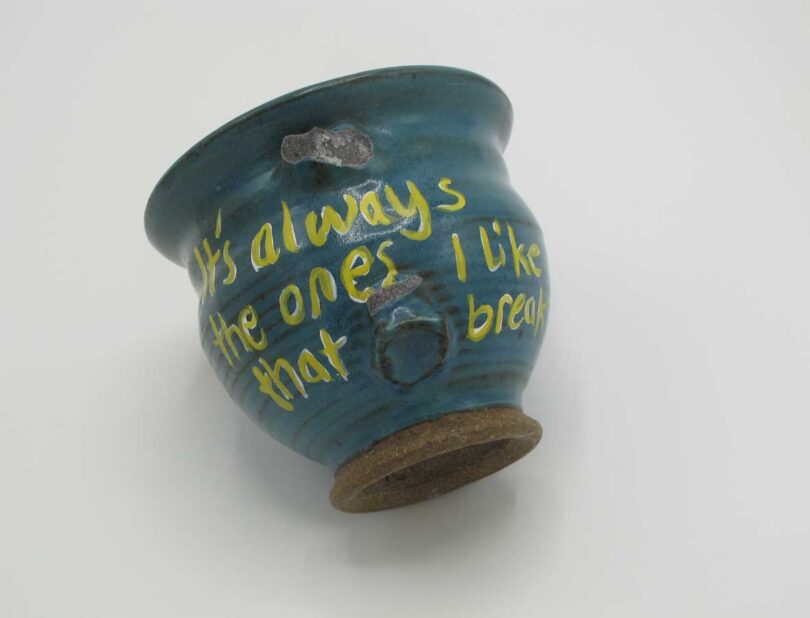

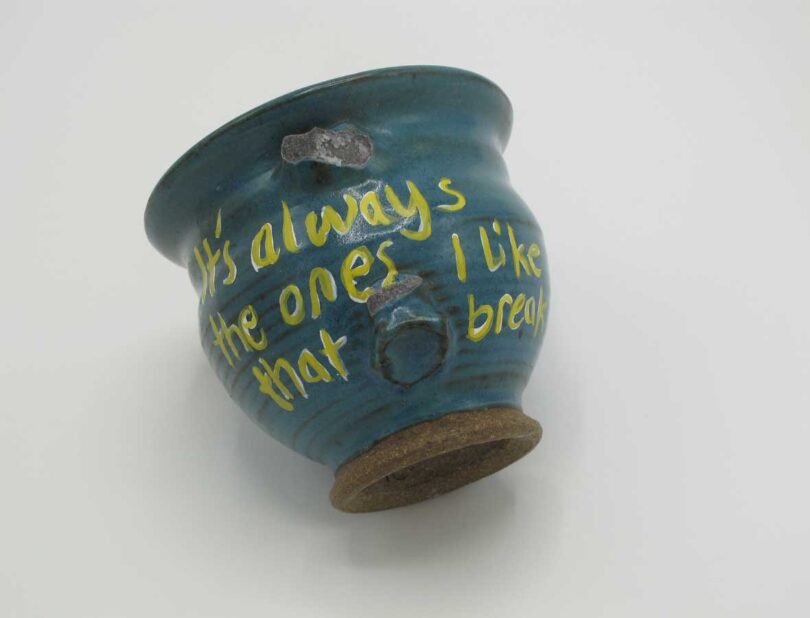

I actually work with a lot of different materials, but one thing I have been doing now for about eight years is exploring ways of repairing ceramics. I call the series Sides to Middle, which is actually a textile phrase (you would cut your old, worn bedsheet down the middle, and sew the edges together to create a new, stronger middle area to sleep on). I like this phrase because to me, it also riffs on writer Rebecca Solnit’s suggestion that hope can help bring ideas in from the fringes to the conspicuous center ground, make them more noticeable. So with this body of work I have been trying to show that we can repair all sorts of things, to show different methods (not always practical ceramic methods) and aesthetics, in objects that we are all familiar with – plates and bowls.

What is the inspiration behind it – where did the idea come from?

I was reading a book called Waste and Want by Susan Strasser – it’s a social history of trash, and in it she spoke briefly about old household approaches to ceramic repair. I started to look more into it, trying out ideas I found in my studio, and through that looking into and testing conservation methods. It really just grew form there.

Which repair techniques are you using and why?

I am a bit nomadic – I have always taken a multidisciplinary approach to my practice, using different materials and drawing techniques from different areas. I am really interested in combining different materials so metals and woods with ceramics, testing out different glues, constructive ways of using plastics, and so on. I also always go back to textiles and textile techniques – darning, patching, binding, stitching.

How did you learn the techniques you use in your work?

Some I learnt at home growing up, particularly the textile techniques and also making and using jigs to support my work. Others I have learnt through workshops and other lessons. But most I have taught myself. I was lucky enough to do a residency at the V&A Museum, where I watched and spoke to a lot of conservators – observing the practices and the objects. I learnt a lot there and came across a lot of techniques I wouldn’t have known about otherwise.

How do your repairs change the function or story of the object?

Sometimes they don’t – they just return it to form, and I like that. Other times the object becomes the carrier of the repair story, it is almost more about the repair than the original object (that is particularly true of my museum/exhibition displays). Ideally, we see the object back in some form of use, with its repair in dialogue with and part of its use story.

How visible or invisible is the repair and why is that important?

I am not intent on my work always being visible. For me invisible or as-invisible-as-possible repairs fit better with post-modern and late-neo-liberal ideas around perfection and aesthetics of commercial goods and clothing. However, this often depends on design. That said, I also really like visible repairs and a lot of my work is visible. I like the discussions they provoke, the stories they tell, and the authorship/signature they provide. I also think visibility helps with overall acceptance of repair as necessary, and it can be a political statement about how or when we chose to discard things. I am really interested in care, and visible repairs make visible the care applied to that object.

How have people reacted to this project or body of work?

Overall positively, although I have had questions about the necessity of it when it can be cheaper to replace things. This is a really good discussion to have – one thing that is often overlooked in repair work is the idea of privilege – having things which are repairable, having the time/materials/tools to do the work, ideas around aspiration and social acceptance.

How do you feel opinions towards mending and repair are changing?

Slowly! But they are changing. I think there is a long way to go before it is a truly mainstream culture though.

What do you think the future holds for repair?

Hopefully lots of it. I think we will see more legislation around repair and waste. France has just shown one pathway by introducing a bonus scheme for people paying to have clothes repaired. And I hope we will see more education schemes around repair – training, apprenticeships, expansion of the conservation discourse, etc. This is starting through ideas like Team Repair who send out kits and tools for kids to learn about repair, but ideally it will also be present in schools, higher ed and so on too. I love mending things and I love seeing others enjoying it too.

This post contains affiliate links, so if you make a purchase from an affiliate link, we earn a commission. Thanks for supporting Design Milk!